Mitigating sovereignty risks without slowing AI innovation

Artificial intelligence is fueling a massive surge in data creation and usage, and with it, heightened scrutiny of data sovereignty policies. Governments and corporations are now grappling with a delicate balance between enabling broad data access to accelerate AI innovation while enforcing protections that safeguard national interests and citizens’ privacy. Expanded access can unlock powerful AI capabilities, but restrictive policies risk fragmenting data ecosystems and limiting technological competitiveness.

In this article, we explore the growing challenges surrounding data sovereignty and highlight how different countries are responding.

Data sovereignty refers to the principle that a nation’s legal and regulatory frameworks govern the digital information that is collected, stored, or processed within its jurisdiction. For IT and storage architects, this requires ensuring that data remains physically located in approved regions, that encryption keys are controlled locally, and that backup and disaster recovery mechanisms comply with jurisdictional mandates. It also necessitates rigorous audit logging and monitoring, along with strict oversight of any cross-border data transfers.

The rise of data sovereignty is driven by growing concerns around privacy, cybersecurity, and geopolitical influence. Several forces are accelerating this trend, including the explosive growth of AI and its increasing demand for large and diverse datasets, cloud architectures that complicate jurisdictional control over information, the continued occurrence of high-profile data breaches and cyberattacks, and intensifying national security priorities tied to global digital-economy competition.

While sovereignty regulations share similar motivations, their implementation varies dramatically across regions. Broadly, policy models fall into five tiers:

Data localization requirements significantly reshape compute and storage architectures by pushing organizations toward more distributed edge computing, limiting flexibility in leveraging global cloud providers, and introducing greater governance complexity for managing AI training datasets across multiple jurisdictions.

Large language models (LLMs) are particularly challenged because their training typically relies on aggregated global datasets. To comply, organizations increasingly employ:

These methods enable compliance but add technical complexity and can degrade model performance.

Many countries are developing data governance frameworks that are modeled on, or influenced by, the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), while tailoring them to suit national priorities. This evolving landscape creates both compliance challenges and strategic opportunities, particularly for sectors reliant on data-intensive technologies such as AI, cloud services, IoT, and 5G networks, as well as highly regulated industries such as financial services and healthcare.

Although most nations are modernizing personal-data laws, differences persist over:

The result is a patchwork of policies that global organizations must carefully navigate. For example:

China enforces one of the world's strictest data localization and sovereignty regimes. Under its main laws — the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), the Cybersecurity Law of the People's Republic of China (CSL), and the Data Security Law of the People’s Republic of China (DSL) — data classified as personal information or important data must generally be stored and processed within China. Cross border transfers of such data are heavily restricted and require government security assessments, official certification, or standardized contracts before any data can leave the country. In short, China treats data as a matter of national sovereignty, tightly controlling international data flows and requiring companies to rely on domestic infrastructure for data related to China.

Russia requires companies that collect data on Russian citizens to store and process that data within Russia, enforcing strong localisation rules under its data-protection and personal-data laws. These restrictions reflect a blend of national-security concerns, sovereignty imperatives, and regulatory control motivations.

Brazil regulates data protection under its national privacy law, the Lei Geral de Protecao de Dados (LGPD), which establishes rules for collecting, storing, and transferring personal data. Although Brazil does not impose broad data localization requirements, it places strict conditions on international data transfers to ensure that foreign jurisdictions provide adequate protections. In some regulated sectors, including finance, health, and government services, domestic storage or tight restrictions on data movement can apply, effectively pushing businesses to maintain local infrastructure. Brazil's approach aims to safeguard privacy and national interests while still supporting participation in global digital markets.

Malaysia is reforming its Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) to align with global standards such as the GDPR and strengthen oversight of cross-border data flows. Regulations in finance and healthcare emphasize local data residency and require approval for offshore processing. Additionally, the government is creating an AI governance framework that prioritizes transparency, accountability, and domestic data control.

Taiwan's Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) follows principles similar to those of the GDPR. While there is no general data residency mandate, regulators may restrict cross-border transfers that threaten national interests or lack adequate safeguards. Sector-specific rules are stricter: payment institutions must host systems in Taiwan, telecom operators are prohibited from sending subscriber data to mainland China, and health-related data is subject to onshore storage and export controls.

The Philippines' Data Privacy Act (DPA) allows individuals to control their personal information and aligns with GDPR principles, such as access and correction rights. For cross-border data transfers, organizations must implement adequate safeguards, typically through contractual mechanisms like Model Contractual Clauses (MCCs), rather than relying on formal adequacy decisions.

Thailand's Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) follows GDPR principles, emphasizing lawful processing, consent, and individual rights such as access, correction, and deletion. It includes specific rules for finance, healthcare, and telecommunications, as well as guidelines for cross-border data transfers.

India is strengthening its approach to data protection and sovereignty through the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 and related regulatory frameworks. While it does not mandate full data localization across all sectors, India places tight controls on how personal data can be transferred abroad and reserves the authority to restrict transfers to specific countries when national interests are at stake. Regulated industries such as finance and payments often face strict requirements to keep certain data stored domestically. Overall, India is moving toward greater digital sovereignty, balancing openness to global data flows with a growing emphasis on national security, trust, and protection of its citizens’ information.

Indonesia's Personal Data Protection Law (PDP Law) follows GDPR-style principles emphasizing lawful processing, consent, and individual rights. It establishes a hierarchical and stricter governance framework for cross-border data transfers, requiring an adequate level of protection or that binding safeguards (such as contractual clauses) from the recipient country. The law mandates the creation of a new Personal Data Protection Institution to supervise its enforcement, which will be directly responsible to the President, a structure that raises questions about the regulator’s independence.

Vietnam's data governance framework is a complex and evolving structure built on the Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) of 2025 and the 2024 Law on Data, which blends GDPR-like protections with strong state oversight. The PDPL mandates consent for data processing, grants individuals rights to access and correct their data, and requires a Cross-Border Transfer Impact Assessment for data transfers abroad. The Law on Data imposes stricter controls on "important" and "core data" related to national interests, often requiring Ministry of Public Security (MPS) approval for core data transfers. Additionally, the 2025 Digital Technology Industry (DTI) Law introduces a risk-based governance framework for AI systems, with the MPS as the main enforcement authority.

Germany maintains one of Europe's most stringent and sovereignty-driven data protection environments, rooted in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and reinforced through national laws and regulator oversight. Rather than imposing broad data-localization mandates like China or Russia, Germany emphasizes legal jurisdiction, strict consent requirements, and accountability for data processors regardless of where data is physically stored. Cross-border transfers are only permitted to jurisdictions that provide adequate protection or with legally binding safeguards such as Standard Contractual Clauses. German regulators and policymakers increasingly view digital infrastructure and cloud services through a sovereignty lens — prioritizing trusted providers, security assurances, and initiatives like GAIA-X that promote European control over critical data assets. This approach balances participation in global digital markets with strong protections for privacy, national security, and industrial competitiveness.

The United Kingdom enforces a comprehensive data protection regime rooted in the UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018, which preserves many of the principles inherited from its time in the EU. The UK does not impose broad data localization mandates, instead relying on strong regulatory oversight, lawful processing, and accountability regardless of where data is stored. Cross-border data transfers are allowed only when appropriate safeguards are in place or when a recipient country has received an adequacy decision from the UK government. Since Brexit, the UK has pursued a more flexible and innovation-focused approach, supporting digital transformation, international trade, and the growth of AI-intensive sectors while continuing to prioritize national security, privacy rights, and trusted digital infrastructure.

France takes a strong and sovereignty-focused approach to data protection, grounded in the GDPR and reinforced by national laws and the oversight of the CNIL, its influential data protection authority. While France does not require universal data localization, it places significant emphasis on ensuring that personal and sensitive data remain under trusted European legal and security frameworks. Cross-border transfers must meet GDPR adequacy or safeguard requirements and can face heightened scrutiny when national security, critical infrastructure, or public-sector information is involved. France actively promotes European digital autonomy through initiatives that encourage the use of domestic or EU-based cloud services, aiming to protect French citizens, institutions, and industries while still enabling participation in global data flows.

The GDPR has become the world's most influential data-protection regime. Its extraterritorial scope means any organization handling EU or UK personal data must comply with stringent requirements such as 72-hour breach notification and major penalties for noncompliance.

An important feature is the EU adequacy model, which allows seamless data flows to jurisdictions deemed to provide equivalent protections. Countries currently recognized include Japan, South Korea, Israel, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, among others. This status strengthens digital trade competitiveness and serves as a regulatory signal of trust.

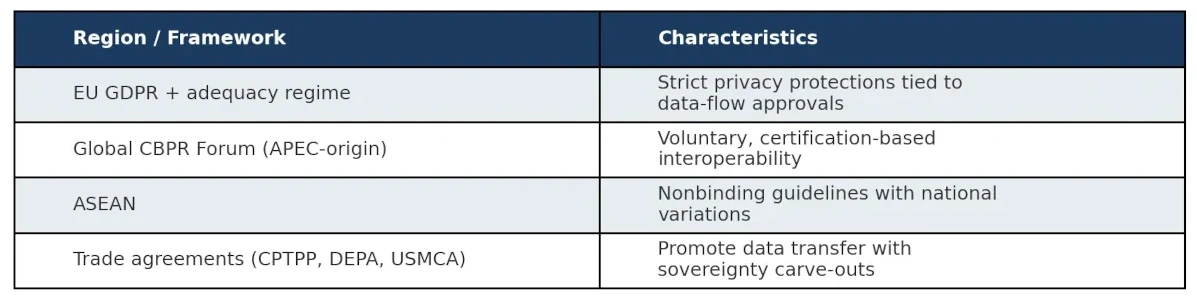

While regional alliances are trying to align governance approaches, no unified global standard exists. Different models coexist:

Next-generation digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and advanced 5G networks are accelerating the global economy’s shift toward data-driven innovation. These systems depend on large volumes of fast-moving data to deliver real-time intelligence, automation, and highly personalized services. As devices and infrastructure become increasingly interconnected, data becomes the essential fuel powering new capabilities in industrial automation, smart cities, digital healthcare, autonomous transportation, and many other sectors.

However, regulatory environments governing data are becoming more restrictive and complex. Privacy frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) help protect consumer rights but can also limit the diversity of datasets needed to train accurate, unbiased AI models. When access to data is restricted or overly sanitized, learning systems may fail to reflect real-world conditions. Data localization requirements add further friction by forcing organizations to store and process information within national borders. This leads to fragmented infrastructure, duplicated costs, and uneven model performance across regions.

Rapid growth in IoT data increases these challenges. Billions of connected devices continue to generate unprecedented quantities of operational and personal information. Organizations must now manage higher compliance obligations, stricter cybersecurity requirements, and increased exposure to privacy risks. Regulatory failures can result in significant penalties. Yet excessive caution can also slow innovation and diminish the value created by intelligent networks.

To navigate these pressures, companies are increasingly adopting privacy-enhancing technologies. Federated learning enables model training at the edge, keeping raw data near its source. Differential privacy protects personal details while still enabling statistical analysis. Secure multi-party computation enables multiple parties to generate insights from encrypted datasets without revealing the underlying information. These approaches help maintain compliance and unlock analytical value, although they often introduce new costs, performance constraints, and operational complexity. The organizations that succeed will be those that align technical architecture, regulatory strategy, and governance maturity to support responsible progress in AI-driven digital ecosystems.

Hyperscale cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud are central to global digital transformation. Yet their global operating models place them squarely in the path of increasingly strict data localization and sovereignty rules. Even when computing resources are deployed within a country’s borders, full compliance is difficult to guarantee. Specific monitoring, administrative, or backup functions may continue to route through offshore systems, and shared operational environments can expose data to cross-border interdependencies that regulators view as unacceptable.

In response, hyperscalers are rolling out new architectures to deliver stronger sovereignty assurances. These include sovereign cloud environments with strict separation of operational control, local data centers and on-premises solutions that keep critical data physically in-country, and enhanced customer control over encryption keys and data residency. However, meaningful constraints remain. For example, U.S.-based providers are still subject to the CLOUD Act, which allows U.S. authorities to request access to data held by U.S. companies irrespective of where that data is stored. This creates ongoing jurisdictional risk even when sovereign models are implemented.

Alongside hyperscalers, a new class of regional and sector-focused cloud providers, often termed neoclouds, is gaining traction. These providers compete by offering deeper compliance alignment, in-country governance, and highly assured data residency, usually operated entirely under domestic legal jurisdiction. They address sovereignty concerns that large global players cannot fully eliminate and are becoming strategically important for governments and regulated industries. However, neoclouds headquartered in the United States, including CoreWeave, remain subject to the CLOUD Act, which limits their ability to provide complete jurisdictional insulation despite strong technical and operational safeguards.

Data sovereignty has emerged as a defining issue in the global digital economy. The rise of AI, pervasive IoT connectivity, and advanced cloud infrastructures has intensified the need for clear controls over how and where data moves. Yet as nations assert greater regulatory authority over information within their borders, organizations must navigate a more fragmented and complex landscape that can slow innovation and constrain the scale advantages of global AI systems.

Regulators, enterprises, and cloud providers are all seeking equilibrium. Governments want to safeguard national security, sensitive industries, and individual privacy. Technology leaders seek freedom to innovate with large, diverse datasets. Cloud providers are developing new sovereignty-aligned infrastructure models, while neoclouds are emerging to serve markets where jurisdictional assurances are paramount. None of these approaches alone is sufficient, and trade-offs will remain unavoidable.

Ultimately, the future of data sovereignty will depend on flexibility, trust, and cooperation. Nations will continue to protect core data assets, but forward-looking policy frameworks must preserve cross-border collaboration where it is safe and beneficial. Organizations that proactively invest in resilient governance architectures — including privacy-enhancing technologies, distributed data models, and multi-cloud strategies — will be best positioned to thrive. Those that treat sovereignty as a strategic capability rather than a compliance burden will unlock the full economic and societal value of data in the age of AI.